Atomic Habits by James Clear is one of the most well-known productivity books out there, and for good reasons: it’s a straightforward and easy read with intuitive insights about transforming the habits we take for granted into deliberate behavior. If you’ve heard of the concept of how the compounding effect of 1% daily improvements yields a return of doing something 37 times better after a year (whereas doing something worse by 1% over that same time period results in a 3% decline), it was probably regurgitated from this book.

I think Clear does a great job providing a structure to first understand our actions before acting on them. There’s a fair amount of frameworks covered, so I’ll be summarizing what I took away, with the intent to apply those techniques deliberately so that I may achieve many of the objectives I’ve set for myself (like learning how to play the guitar, read more books, and improve as a programmer).

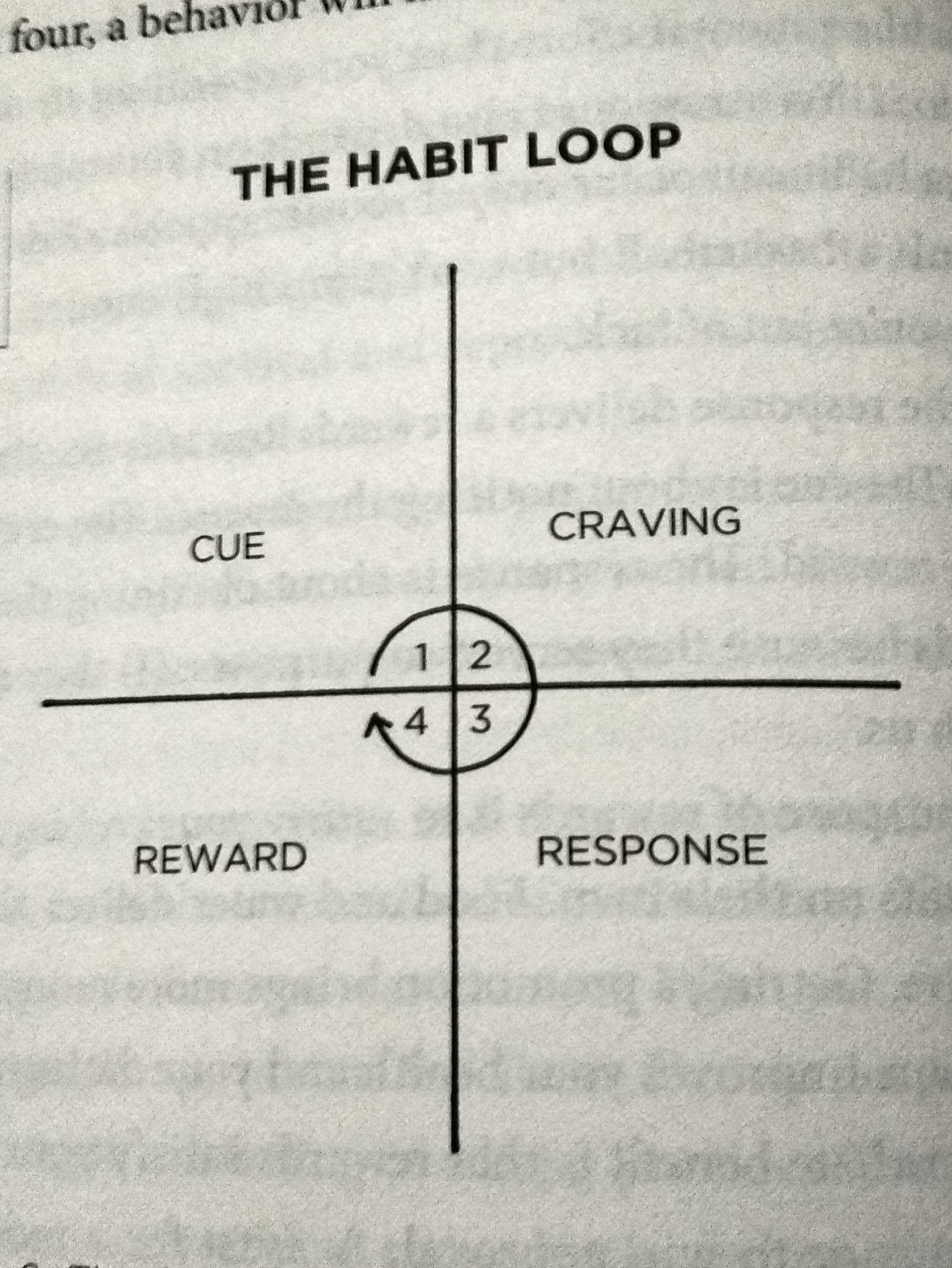

1. The Habit Loop

The Habit Loop (HL) describes the cycle by which habitual behavior is enabled, often without deliberate intent. The HL is described in two phases and four stages: 1. Problem Phase: “what needs to change” 1.1 Cue: Often unconscious triggers which initiate a behavior. 1.2 Craving: The motivational force behind habits. 1. Solution Phase: “the action required towards achieving desired changes” 2.1 Response: The thought or action performed. 2.2 Reward: The end goal of a habit. The HL is the framework by which Clear outlines his strategies for creating new, better habits, and for breaking old, detrimental ones.

2. The Four Laws of Behavioral Change

The four laws of behavioral change target each stage of the HL. They’re outlined as follow:

| HL Phases | Creating Good Habits | Breaking Bad Habits |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Law - Cue | Make it obvious | Make it invisible |

| 2nd Law - Craving | Make it attractive | Make it unattractive |

| 3rd Law - Response | Make it easy | Make it difficult |

| 4th Law - Reward | Make it satisfying | Make it unsatisfying |

Make it obvious

One of the core concepts of the book is the concept of ‘habit stacking’, which is an implementation of intentionality by identifying a current habit and building another on top of it. Clear describes it using the following formula:

Habit stacking is a powerful concept, and what enables the compounding return of daily habits over the long-term. It also proves to be less daunting than to adopt new habits from scratch, and improve the odds of sticking with said new habits. Another implementation formula that I like is:

This is helpful to remember applying developing habits consistently and deliberately, especially for someone like myself who’s often scatterbrained. The key here is consistency until the habit becomes normative behavior, something which, thinking back, was the formula drilled into us as children by our parents (“I will [BRUSH MY TEETH] [BEFORE GOING TO BED] [WHEN I CHANGE INTO MY PAJAMAS IN THE BATHROOM]”, for example). What’s revealing about Clear’s book is thinking back about each little daily ritual and thinking back about where they originated, which often began in childhood. Just goes to show how important habitual behavior during the stage of childhood development is to functioning adulthood. I also really liked Clear’s emphasis on preparing an environment which is conducive to cuing into a habit rather than relying on intrinsic motivation, which is often fleeting and flimsy. “Small change in what you see can lead to a big shift in what you do” is a pretty powerful idea to gear one’s mindset reflectively. I think that it’s important to unload as much mental clutter externally. For me, using a digital calendar that I can access on my phone easily has considerably improved the retention of many habits compared to a physical annotation board that I could only consult at my desk. It’s a virtuous cycle: to effectively stack habits, your surroundings have to reinforce the objectives of what you want to become, and not merely what you want to achieve.

Make it attractive

One idea I took to heart in this section, something perhaps quite obvious, is the mindset shift from “having to do” to “getting to do X”. I mean, of course, you can’t always sugarcoat having to do something, especially if you’re in an economically vulnerable situation. In my case, I’m fortunate enough to be able to take some of the ‘hardest’ aspects of my daily routines and view it in a positive light. Even thinking back to a time when I was “dragging myself” to an unfulfilling and dreary office job, I’m glad that I had the intuition to use my depressing commute as a time where “I got” to do a lot of leisurely reading. And looking back at those times, these were some of my most prolific periods as a reader. So whenever it’s appropriate to do so, I welcome the “I get to” mindset, as it grounds my actions and valorizes my decision-making, even under tough circumstances.

Make it easy

Here Clear pointed to something that I’ve kept in mind for a long time: that being busy isn’t being productive or conducive to quality work. This applies to the procrastination mindset, which tricks the mind into the illusion of being productive but instead creates “motion [which] makes you feel like you’re getting things done”. Personally, I often catch myself into the motion of procrastination by cleaning (anything) instead of working on the thing that is repelling me from getting it done. It’s better than watching Youtube videos, sure, but I’d much rather be deliberate in every action that needs to be done regardless, instead of retreating into something adjacently productive because I am actively seeking to avoid an even more daunting obligation. Another key advice is the idea that “the amount of time performed on a habit is not as important as the number of times that it has been performed”. This is definitely true: 5 minutes of daily practice is a hundred times better than an hour of sporadic practice. This is something I’ve experienced from martial arts (although not having practiced in years, I’m still capable at the drop of a hat of doing a double jumping 360-degree round kick from the sheer amount of time I’ve practiced it, it’s simply imprinted onto my muscle memory), or my (current) failing attempts at learning chord transitions on the guitar.

Make it satisfying

“What is rewarded is repeated. What is punished is avoided”. Sadly our monkey brains reward us for bad habits. In my case, those might be the dopamine release of savoring the texture of crunchy, salty chips, even though my acid reflux will always punish me for it. “The brain’s tendency to prioritize the present moment means you can’t rely on good intentions”. We tend to be unkind to our future selves for immediate pleasure. Therefore, a framing of habit formation is not towards ‘meeting an objective’, but towards a transformation of who we want to be. I.e., instead of ‘learning the guitar’, I want to become a musician. Instead of ‘losing weight’, I want to be someone athletic and knowledgeable about self-care. But for this transformation to happen, the ‘virtuous cycle’ of habit stacking must not be allowed to be corrupted by the entropy of everyday life. Meaning that “missing once is an accident. Missing twice is the start of a new habit”. The integrity of commitment is what separates amateurs from the pros. Another profound insight I really liked is Clear’s mention of ‘Goodhart’s Law’:

This is something I can especially appreciate as a data analyst, where decision-making can become pigeonholed by KPIs and metrics that only tell a part of a larger, richer, more complex reality. For myself, I have a weight loss goal, so my weight has been a quantitative measure of my progress for a long time. But as Clear points out, it’s also about how a new habit makes one feel, about the larger picture of improving one’s quality of life, the richness of forming bonds, the self-satisfaction of the process in itself. Thankfully, even though I have not yet met my weight target, at the very least I’ve profoundly enjoyed rediscovering the joys of swimming years after I had practiced any. We tend to place empirical values on pedestal towards measuring the ‘true’ worth of something. We’re humans, not fucking machines, and we are not ascribed to the endless process of bean-counting the commodified value of our self-worth. There is no shame in feeling, even when we are not at our best.

3. Staying Motivated

The Goldilock rule states that working on challenges of just manageable difficulty (within the realm of one’s immediate capacity) is crucial for maintaining motivation. For language acquisition, for instance, it can be very frustrating to either be stuck doing something very easy, or far too advanced. This means that with any skillset one is trying to master, you need to be at the baseline of your current abilities, something I suspect people struggle to define properly. The other enemy of motivation is boredom: although, in itself, boredom isn’t the problem. Boredom is expected from routine. Rather, it’s overcoming the boredom derailing the force of habit that must be kept in check. Craving is a powerful intuition, hence, adding some variety to routines can be helpful to overcome it. Also being resigned, and understanding that being an adult often means having to do shit you don’t want to. Or, as we’ve learned, getting to shovel the shit so that our garden of virtues may grow. Finally, one last mnemonic formula to keep in mind:

If mastery in a skill or subject is what you seek, reverse engineer what are the habits that contribute to success, and what is the work that needs to go into it. Mastery is not a continuous, exponential line, but a stepwise increase, different floors at which the ‘game is played’. In conclusion, perfect the art of self-awareness, be kind to yourself in your failures, allow yourself to take pride in your progress, and move from an objective-oriented mindset towards a system-oriented one. The teacher is the enemy (an insightful idea quoted in the sci-fi book Ender’s Game). If the accumulation of bad habits is your own worst enemy, learn from it, and fight it, and become stronger each day. It sounds like motivational drivel speech, but there’s a genuine ring to it.